Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength. (Mark 12:30)

Anyone ever read Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer? A true story. Sean Penn made a move out of it. [Spanish]

In 1990 a young northern-Virginia man wandered west, into the wilderness, trying to unravel the mystery of life. He had nothing, lived on what came his way, experienced the enchantment of the earth’s beauty—as if every day could be the last. He shared a little bit of the total freedom of St. Francis.

This young man also thoughtlessly left his family behind—his parents, his beloved sister; his friends. He underwent a complete separation from all the ties that bound him. In order to find…? The truth. God.

The story utterly captivates me because Chris McCandless and I have so much in common. Born around the same time; grew up within twenty miles of each other; got good grades and ran cross-country in high-school.

And both of us did our share of hitchhiking around America in the years 1988-1992. In those days, not a lot of people thumbed it, like they had back in the 50’s and 60’s. So it was a little risky. That said, I suppose it’s a lot harder to get rides now than it was thirty years ago.

God. He’s everywhere. All the time. Silently omnipotent. Inscrutably immediate. What else could possibly matter, besides God? He calls. How could any of us truly be himself or herself without trying to listen, to follow, to find Him? Without abandoning everything for Him?

Everything comes from Him, and everything tends toward Him. He fashioned everything and governs all. Some fatalistic pagans think the whole cosmos and our lives are just a meaningless game that God plays. But that’s not fair—to us. We have a serious purpose. Vocational discernment is no meaningless farce. Each of us exists for a reason, and each of us must find that reason—or risk losing our very selves.

Anyone have a wall map of the US? With a separate map of Alaska tucked into one corner? (Hawaii in the other corner.) Anyone ever bothered to compare the scales of the continental US map versus the Alaska map? You know: one inch = a hundred miles, or two hundred.

Anyway, on my wall map, the scale for Alaska is double the scale for the lower forty-eight. Alaska ain’t no chicken-scratch Canadian backyard. Texas, California, and Montana, spread out next to each other, could all fit inside Alaska. Alaska is 9/10th the size of Mexico.

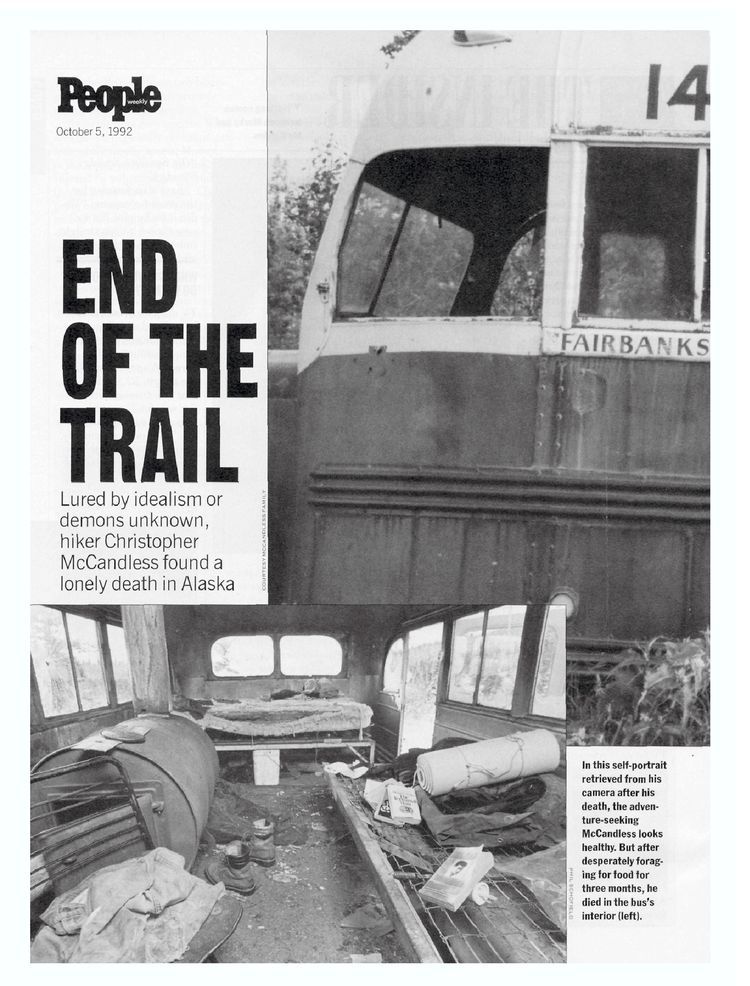

At age 22, Chris McCandless hitchhiked, worked odd jobs, got to know people from all different walks of life—then wound up in solitude in the northern reaches of the Denali Nature Preserve in the Alaska interior.

Certainly a lot of us can relate to some of that. The business of coming of age, exploring the world, figuring out who you are. At age 22, I, too hitch-hiked, worked odd jobs, got to know people from all walks of life. But I didn’t wind up in Alaska. I’ve never been to Alaska. I wound up in RCIA.

The crucifix was my Alaska. A crucifix doesn’t encompass the size of California, Texas, and Montana combined. Rather, it’s the size of a single human being. Same size as all of us.

Yet the crucifix unites heaven and earth, eternity and time. It unites solitude and solidarity. Alaska is a lonely place—seems like one, anyway. But the Christian Church? No, not lonely. The crucifix unites God and man. Jesus Christ has united all of this—the whole cosmos He made—in love.

Finding God’s will. You have to follow the rules. Pray, go to Mass, obey the Commandments. But then your calling comes as a pure gift. At 22, by the pure grace of God, I knew He was calling me to become a priest. I knew that without any doubt. Though to this day I still can’t say that I fully know what a priest even is.

I know a priest lives from Jesus and for Jesus. Like everyone. Every human being who has ever lived and died, or who will ever live and die—all live from Jesus and for Jesus.

Jesus had a vocation: to live from the Father and for the Father. Jesus of Nazareth consummated human life as religion. When I was 22 my friends told me I was ‘strangely religious.’ By the time I joined the Church and then went to the seminary, they gave up on me as a fanatic, a madman.

But what else is there? Jesus wasn’t “too religious.” He lived a pilgrim life in which every single breath communicated eternal love. He lived His whole life on earth as one big crucifix of union with the Father.

Chris McCandless didn’t make it. He neglected to consider that Alaskan rivers swell a lot in the summer, as some of the snowpack melts off. He couldn’t make it back the way he had come; he ran out of provisions. He breathed his last six months before his 25th birthday. May he rest in peace. There’s a little, kind-of shrine to him, in Healy, Alaska. A few hundred people visit every summer.

At the exact same time—when McCandless was running out of food and strength—I met with a Catholic priest for the first time in my life and started to learn the Catholic faith and get ready to enter the Church. To God be the glory.