William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act I, scene 1

—

[This is Part II of my series in honor of my dad, on the fifteenth anniversary of his death. Click HERE for Part I.]

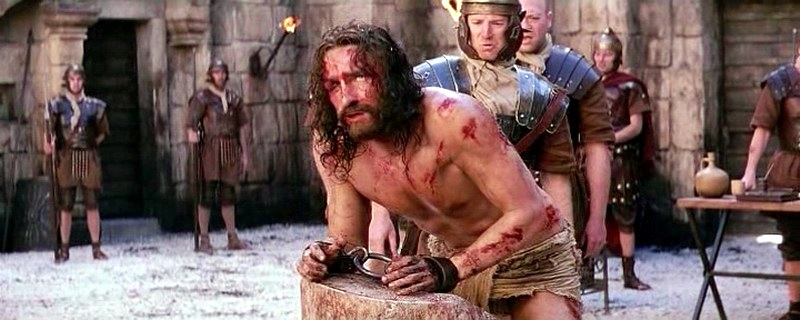

During the midnight hour on Sunday, March 3, 1991, three Los Angeles patrol officers brutally beat a defenseless man. The three officers acted under the direction of a sergeant.

The officers’ names are: Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno. The sergeant was Stacey Koon. The defenseless man was Rodney Glenn King.

George Holliday made a video of the beating, from the balcony of his apartment across the street.

King had two passengers in the car with him. The police detained the passengers at the scene briefly, but then released them without taking them anywhere.

Holliday must have crossed the street and told the passengers–Rodney King’s friends–that he had videotaped the beating. One of the passengers told King’s brother, Paul, about the videotape.

The following day, both Paul King and George Holliday went to the police to report the unlawful beating. Paul King mentioned the videotape.

Both complaints were immediately filed as “requiring no further attention” by the LAPD. Holliday and Paul King knew they had been totally blown off.

So Holliday then took his videotape to KTLA, and within 36 hours the rest of America had seen the beating on the news.

For freedom Christ has set us free (Galatians 5:1). But a criminal forfeits that freedom and subjects him- or herself to compulsion. By lawful authority.

I.

Rodney King had subjected himself to compulsion by lawful authority, in the midnight hour of Sunday, March 3.

A California Highway Patrol vehicle saw King’s Hyundai going 120 mph on the San Fernando Freeway. The officers tried to pull King over. He had a duty to obey, to stop on the shoulder. He did not do so. He led the officers, and other patrol cars that joined in pursuit, on an eight-mile chase.

By doing this, King apparently committed the crime of “felony evading.” (He was never charged for this, or any other crime.) When King finally pulled over, next to a park, the officers in pursuit identified the situation as a “high-risk stop.” Which means that they had the right, in the interest of their own safety, to order all the occupants of King’s car to get out with their hands up. King and his two friends had a duty to obey such an order.

At this point in the unfolding story, we reach the moment where we might question the way the officers tried to compel King and his passengers, under the color of lawful authority.

It apparently was the policy of both the California Highway Patrol and the LAPD, at “high-risk stops,” to order the motorist and passengers to lie down flat on the pavement, arms spread wide, face turned away from the approaching officer.

This was to allow for a relatively low-risk approach by the officer, to handcuff the motorist, and any passengers.

This was to allow for a relatively low-risk approach by the officer, to handcuff the motorist, and any passengers.

(Whether or not this policy of demanding a “prone position” has changed since 1991, I do not know.)

Granted, if you have led police officers on an eight-mile high-speed chase, I think we can say that you have forfeited your bodily freedom at least for the moment, and you must submit to handcuffing.

But ordering someone to lie down, prone on the asphalt, face turned away? Maybe that crosses a line out of the realm of officer safety and into the realm of undue humiliation?

Anyway, as a practical matter: At about 12:40am on March 3, 1991, Rodney King did not comply with the order to lie prone on the ground, and for good reason.

For one thing, King likely did not hear the order over the sound of the helicopter overhead. Secondly, he would have had trouble understanding the word “prone,” even if he did hear the order. Lastly, while he did get down on all fours, he did not appear able to lie the whole way down. Was it because he was too proud? Maybe. Was it because he was intoxicated and confused? Almost certainly.

King never made any violent action; he posed no threat. He never even directly evaded getting handcuffed. He was pretty clearly drunk and confused. And then suddenly he was in fear for his own life.

II.

Officers Powell and Wind proceeded to beat King mercilessly with their metal batons. Officer Briseno kicked him. Sergeant Koon gave the orders.

As we mentioned, George Holliday captured it on tape. The overwhelming majority of the people who saw the tape in the ensuing days regarded the police officers’ actions as criminal.

As we mentioned, George Holliday captured it on tape. The overwhelming majority of the people who saw the tape in the ensuing days regarded the police officers’ actions as criminal.

According to two different polls, 90% of the residents of Los Angeles County saw Holliday’s videotape, and 92% of those who had seen it believed the officers had used excessive force. Eighty percent thought the officers had committed a crime.

The officers, in other words, put themselves into the position that Rodney King had put himself in, by speeding on the freeway and not pulling over. The officers made themselves subject to compulsion by lawful authority.

Lawful authority did not respond with violence this time, but with due process. An L.A.-County grand jury indicted the four officers for criminal assault.

Due process requires a fair trial. The long, hot summer of 1991 saw some stunning developments in the pre-trial business.

III.

I don’t know who made the decision to try all four officers together. I don’t know if putting them on trial separately was ever even considered as an option.

The decision in Minneapolis last year to try Derek Chauvin separately from the other officers involved in George Floyd’s murder–that certainly seems like a wise decision, indeed.

The circumstances in L.A. three decades ago were different. Sergeant Koon never personally laid a hand on Rodney King. He did, however, order his officers to beat the defenseless man mercilessly.

I would say that putting all four officers on trial together proved to be the first, and probably greatest, of the prosecution’s mistakes. That is, if it was their mistake. Perhaps it was simply a fait accompli, for legal reasons I don’t understand.

By putting the officers on trial together, the prosecutors wound-up having to contend with four different, highly skilled defense lawyers. The defense ultimately managed to dominate the trial. If the officers had been tried separately, maybe that wouldn’t have happened.

The Superior Court of Los Angeles County assigned the case of People v. Powell et al. to Judge Bernard Kamins. (In California, the trial courts are called “Superior” courts.)

The defense immediately petitioned to have the trial moved outside of Los Angeles, on the grounds that the officers could not get a fair trial there.

At that time, Los Angeles County had 6.5 million eligible jurors. For the officers to have received a fair trial in that county, the court would have had to find twelve among those 6.5 million who could listen impartially to testimony and review evidence, leaving a final conclusion about guilt or innocence until the end.

Jurors must presume criminal defendants to be innocent of the charges against them, then wait to see or hear proof, proof that overcomes every reasonable doubt about the defendant’s guilt.

California law stipulates that a criminal trial should occur in the county where the crime took place, unless a compelling reason calls for a “change of venue.”

The defense argued that the daily news coverage of the event had “contaminated” the objectivity of the L.A.-County jury pool.

Judge Kamins concluded that this was not a compelling reason to move. Because: the same could be said about the jury pool in every county in California.

They simply could not conduct the trial in a county where the potential jurors would show up for duty not having heard about the case. No such county existed. Therefore, this was no reason to change the venue.

…As spring turned into summer, Judge Kamins became ever more eager to move the trial forward.

I don’t presume to know the judge’s mind, but what little I know about the steps he took lead me to see him as a humble, practical man. He recognized that the best thing for everyone involved was to move the trial forward as expeditiously as possible. But the judge’s humble practicality got him into trouble.

The defense insisted on a change of venue and appealed over Judge Kamin’s head, to the California Court of Appeal.

Kamins had set June 19 as the day to begin the trial. On June 12, the Appeal Court put an “indefinite stay” on moving forward with jury selection, until the higher court had considered the defense petition for a change of venue.

Kamins tried to negotiate his way out of the impasse by putting a possible change of venue back on the table for discussion by the parties. The judge communicated informally, departing from the strict rules that govern court communications. It seems clear that Kamins did this in order to get the trial moving sooner rather than later. But his effort backfired completely.

The defense petitioned to have Judge Kamins removed, on the grounds that his off-the-cuff communications had given the impression that he was partial to the prosecution.

In high summer 1991, the California Court of Appeal made two decisions that deserve to go down in infamy.

On July 23, the Appeal court unilaterally ordered a change of venue. That particular Appeal Court decision is known as Powell v. Superior Court.

In this decision, the Court of Appeal granted that the “media saturation” argument did not suffice to compel a move. But the Court of Appeal introduced another consideration: the contamination of the L.A.-County jury pool by political allegiances to either the mayor or the police chief.

A “coup,” so to speak–put into motion by the police commission, and backed by the mayor–had tried to oust Chief Gates. The City Council protected the chief, and the “coup” failed.

But:

Neither the mayor nor the chief were directly involved in People v. Powell et al.

And:

All other political issues in L.A. paled in significance to the trial itself. The allegiance of the citizens was not really to either Mayor Bradley or to Chief Darryl Gates. If either of those two gentlemen had suddenly moved to Tahiti, it would not have had anywhere near the political impact that the ultimate verdict of this trial would have.

The Appeal Court’s stated goal was to prevent the “average person on the street” from thinking the trial unfair. So, on August 21, in Briseno v. Superior Court, they removed Kamins from the case.

Fall arrived, and the Appeal Court’s two interventions had delayed the trial by six months. Courtroom testimony didn’t actually begin until a year after the beating. And that testimony unfolded in front of a Ventura-County jury that had not one single black person on it.

Ironically enough, it was the Appeal Court itself that managed to make the average person on the street start to think that things were not right, not fair, not above-board. Something rotten in the state of Denmark, as Hamlet put it.

As we try to understand these chapters, we should remember that we have insights into the fertilization of a human egg by human sperm, as well as the formation of a human embryo and its development–insights that St. Thomas did not have.

As we try to understand these chapters, we should remember that we have insights into the fertilization of a human egg by human sperm, as well as the formation of a human embryo and its development–insights that St. Thomas did not have.

I could do it because of love. My dad taught me that love.

I could do it because of love. My dad taught me that love.

In the “old days,” the bishop would deal with you personally to orchestrate the cover-up of crimes committed against you. Now, the lawyers run the whole show, and the bishop treats you as if you don’t exist.

In the “old days,” the bishop would deal with you personally to orchestrate the cover-up of crimes committed against you. Now, the lawyers run the whole show, and the bishop treats you as if you don’t exist.