In northwest Washington DC, there’s a large apartment building set back from Connecticut Avenue on Van Ness Street. For years, the building was known as The Consulate, then a new owner changed the name.

In January a young man named Raymond Spencer rented an apartment in the building, with a balcony that overlooked Edmund Burke School.

—

My mom taught history in that school for a quarter century. She played a key role in making the school what it is. When she retired in 2005, they named a classroom after her. The alumni magazine highlighted her on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the school’s founding. (Burke began in 1968.)

My mom taught history in that school for a quarter century. She played a key role in making the school what it is. When she retired in 2005, they named a classroom after her. The alumni magazine highlighted her on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the school’s founding. (Burke began in 1968.)

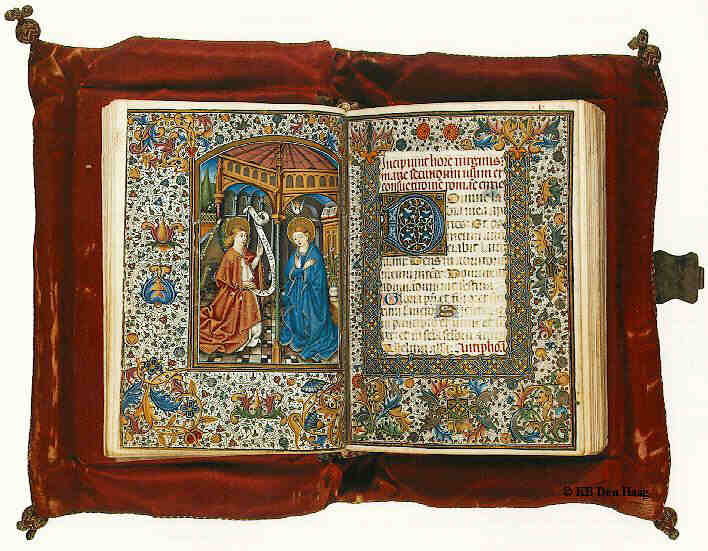

Burke was like a second home to our family. The pedestrian bridge in the photo connects what they call the “new” building, on Connecticut Avenue, with the “old” Upton Street building.

But a quarter century ago, there was only Upton-Street Burke, and we called half of it the “new building.” I remember looking at the muddy construction site for the addition to the original building, out of the back seat of our 1976 Dodge Dart.

I was a student at Burke 1986-88, my brother 1985-1990, my cousin 1988-1991.

We typed the original student government “constitution” on the 1985 Apple Macintosh I had in my room during high-school. When I was president of the student body, the co-founder Dick Roth and I sat in his office and came up with the mascot name–the “Bengals.” I secretly made a copy of my mom’s key to the building, and my friends and I would sneak in and brew coffee in the faculty lounge late on Saturday nights, and sit and talk like grown ups.

—

Nine days ago, Mr. Spencer transported a large suitcase full of heavy weaponry into his apartment in The Consulate. The following day, at the time of school dismissal, he opened fire on the Burke pedestrian bridge over the alley, and at the carpool lane below.

The shots shattered the windows of the pedestrian bridge. But, praised be the Lord Jesus Christ, no one got killed.

Except Spencer himself, that is. He had set up a camera outside his apartment door. When the police came down the hallway to apprehend him, he killed himself.

Spencer’s shots did injure some people. May they soon recover. And of course there’s the trauma inflicted on everyone in the building at the time. They had to run for cover and hide for hours, until the police got to Spencer.

They handled it. Brave kids, brave teachers.

—

Why did Spencer do this? The Head of School has announced that the shooter had no “known connection” to Burke. No known connection, that is, other than having an apartment across the alley for four months, and then opening fire at the school one Friday afternoon.

Spencer knew what he was shooting at. While his loaded gun sat on his tripod, he submitted a revision to the Edmund Burke School Wikipedia page. He wanted to add the shooting to the school’s history.

I, for one, cannot see this crime as “another school shooting.” It’s a distinct crime, committed by a particular criminal, with unique individual victims. In a particular place that, for me, shimmers with memories.

Did Spencer rent his apartment in January, and only then realize that his balcony afforded a line-of-sight to a school, a school which he later learned bears the name Edmund Burke? Did he then at some point decide, in a haze that we probably will never understand, to shoot at the school?

Or did he rent his apartment because it afforded him the opportunity to shoot like a sniper at a particular school he wanted to shoot at, namely Burke?

Maybe we will never know. But there must be clues out there somewhere. May the police find them. Knowing the truth about this would help me. I imagine it would help Burkies in general.

—

Back in the 80’s, a mugging or two took place in the alley between Upton and Van Ness. But generally it was safe. I always felt completely safe.

I remember being in the alley one evening in the spring of ’87, at sunset. Then I stepped into the back door of the school, where there was a payphone. I called a girl I had a crush on, who went to Woodrow Wilson High School on Nebraska Avenue.

I wanted to tell her to look at the lovely sky. The crescent moon and the first stars of the night glittered in an arc, in the waning sunlight.

That payphone is long gone, of course. But I hope the day comes soon when a Burke boy gets to stand in the alley, without a care in the world, and see a sunset like I saw, and use his phone to make an Instagram of it, to impress a girl. I hope that day comes soon.

I think I mentioned before how I served as Cardinal-Archbishop Theodore McCarrick’s deacon on a couple occasions during the Lent and Holy Week of my tenth anniversary as a Catholic.

I think I mentioned before how I served as Cardinal-Archbishop Theodore McCarrick’s deacon on a couple occasions during the Lent and Holy Week of my tenth anniversary as a Catholic.