You. Your books. Your thoughts. And the mountains, hills, bugs, grass, wild flowers, birds, creeks, rivers.

Chris McCandless finished college, then set out west. He longed for the solitudes of Alaska. He had made himself poor, like St. Francis and the Lord Jesus before him. Chris gave away all his money and abandoned the middle-class existence for which he had been carefully groomed.

He had a car, but soon he dispensed with that, too. He had no plan exactly, just a dream. He renamed himself Alexander Supertramp.

He rowed down the Colorado River to Mexico. He hitchhiked and hopped freight trains up and down California, then out to South Dakota. He made some friends who still have not forgotten him. He practiced celibacy. He worked the fields and grain elevators with a combine crew at harvest time. And at a northern-Arizona McDonald’s for seven months.

He chased his dream. Solitude in the Alaskan bush.

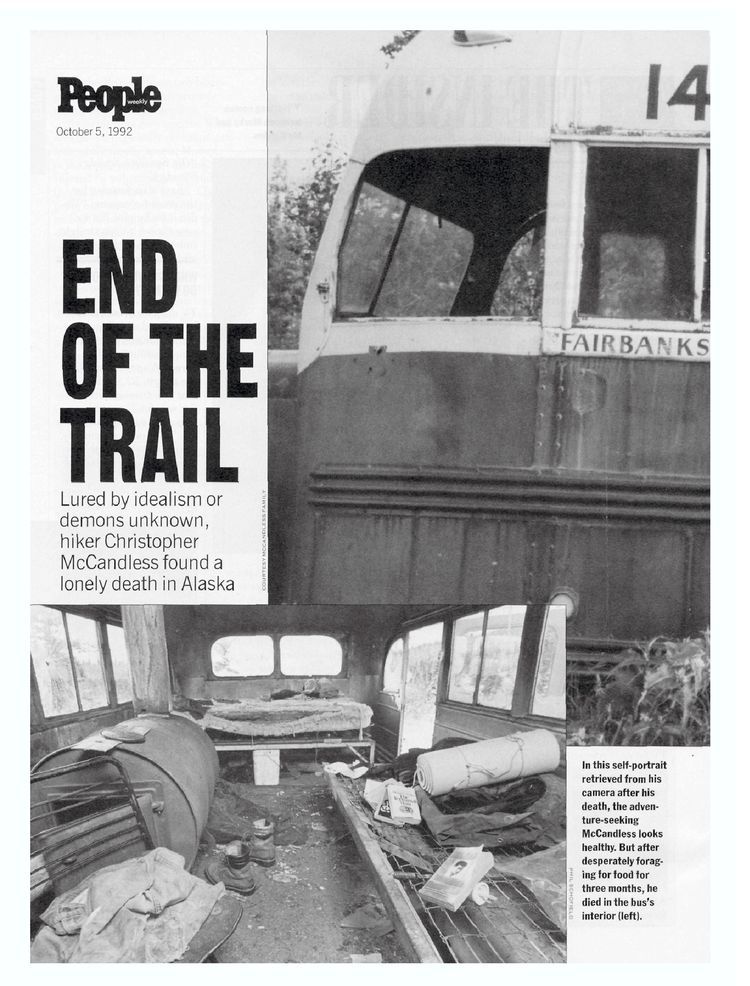

In April of 1992, he hiked out. He had thumbed his way to a trailhead north of Mount McKinley (aka Denali). He had provisioned himself. Minimally. By reading and practice, he had acquired no small amount of survival expertise.

He lived until August.

Before Chris succumbed to starvation, brought on by two mistakes he made, including eating seeds he should not have eaten, he wrote a farewell note: “I have had a happy life and thank the Lord. Goodbye and may God bless all.”

Award-winning writer Jon Krakauer became, by his own admission, “obsessed” with McCandless. Krakauer wrote the definitive account of these events, Into the Wild, published in 1996. Sean Penn made a movie version, released in 2007.

I can tell you that I will read everything Jon Krakauer has ever written and will ever write. Or I will die trying.

Into the Wild has everything it should. A meticulous reconstruction of events, narrated with soaring prose. Careful consideration of all the available botanical literature. The history of other cases of wild, youthful wandering, including Krakauer’s own. Above all: Into the Wild humbles itself before the mystery of this young man’s life and early death.

When it comes to final judgment about McCandless, you can go one of two ways. Sean Penn goes one way with his movie version: Alex Supertramp, the cult hero of Seattle grungers. He lived free. He died young, because his parents, and society, are evil.

Now, I love Eddie Vedder as much as the next guy. (He provides the heartbreaking, just-about-perfect movie soundtrack.) But Sean Penn’s take on what happened does not correspond with the actual facts. McCandless did not have vicious ogres for parents. Just your usual, run-of-the-mill, screwed-up type of people.

Krakauer portrays them much more honestly than Penn. And Krakauer writes about the peace a man can find when he realizes: my flawed father is a fellow human being, like me. He needs mercy, like me. Penn’s movie never gets there.

The other way you can go to judge McCandless: A selfish idiot who got what he deserved for tempting fate and Mother Nature. A son who did his parents very, very wrong. Who wronged all his loved ones, especially his sister. (She’s the most-beautiful character in the movie, giving Chris the benefit of the doubt at every turn.)

Most actual Alaskans–the people who know how to survive there–take this view: Chris McCandless, dumbass.

But Krakauer won’t dismiss the protagonist he calls “the boy” that way. Because it’s inaccurate.

McCandless broke his parents’ and his sister’s hearts. But they themselves refuse to hold it against him. Krakauer knows enough about adventuring in the wild to recognize: this boy was no idiot. He made mistakes that others might have made. (Mistakes that he himself, Jon Krakauer, might easily have made, the author humbly admits.)

McCandless took risks that cost him his life. But taking risks is part of…

…following a “vocation.” Finding your calling. Finding yourself. Finding God. No one every actually found God without risking his or her life.

Documentarist Ron Lamoth also chronicled McCandless’ life and death on film. Lamoth uses a phrase that struck me as a little odd. McCandless, Lamoth, and myself: we all came to birth within two years of each other. Lamoth refers to our generation as “free-spirited Generation X.”

Odd because: The Baby Boomers who watched us come of age would not call us “free-spirited.” To them, we looked like Leave-It-To-Beaver Cleavers with Blackberrys. (We still do look that way to them.)

But Lamoth is right, when you look at our early-1990’s “free-spiritedness” in another way.

Our beloved land, and the world at large: it was a lot more wide-open and free in 1992 than it is now. We feared far fewer boogeymen back then. We allowed ourselves to rely on the kindness of strangers. Much, much more than today’s twenty-year-olds can.

To you, dear young people, I apologize for this. On behalf of all us idiots who let the world get this way. We could have taken steps to keep your world freer, calmer, kinder, and more wide-open. But we were idiots, and didn’t take them.

…McCandless did not want to stay in the bush into August. He had broken camp, and headed for town (and communication with other human beings), in July. But he had not anticipated that the stream he had crossed in April would have swelled into a raging river at midsummer–because of snowpack melting on Denali. This was his first big mistake. (Then, in his hunger, he ate the poisonous seeds, which destroyed his digestive system).

My point is: he did not commit suicide. If this or that little thing had occurred to him, at this or that crucial moment (like, ‘Let me get a topographical map before I head out there.’), he might have a wife and kids in the their early twenties right now. He might teach literature somewhere. Or he might be a priest.

May God rest him. Having read Krakauer’s standard-setting account of things, I now number Chris McCandless among my friends in the realm beyond the peak of Denali.

If only I’d had Catholic parents, maybe I’d have the name “Irenaeus…” But you can’t get any better than St. Mark for a baptismal patron.

If only I’d had Catholic parents, maybe I’d have the name “Irenaeus…” But you can’t get any better than St. Mark for a baptismal patron.