I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and fourth generation. Deuteronomy 5:9 (See also Exodus 20, 34:7, Numbers 14:18.)

In those days they shall no longer say: ‘The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are on edge.’ Jeremiah 31:29. The son shall not suffer the iniquity of the father. Ezekiel 18:19

—

Last week, Georgetown University and the Jesuits apologized for participating in slavery.

The apology happened in the same beautiful hall where my dear historian mom delivered the commencement address, and then I received my high-school diploma. Footsteps away: the office in which, a couple years later, I first spoke with a Catholic priest. Across the courtyard: the chapel where I received Confirmation and First Holy Communion.

And GU/Jesuit history is our Richmond-diocese history, too. The same slave-selling Jesuit whose name they just stripped off one of GU’s oldest buildings also gave the Vespers sermon at the dedication of St. Peter’s parish church in downtown Richmond.

The Catholic Church in the U.S. has an antebellum past. Before the mass migration from Europe that made us an overwhelmingly poor and urban people, we had an earlier chapter–which unfolded primarily in the south, with black slaves.

When I first began the path to the priesthood, I spent ten months in the novitiate of the Maryland province of the Jesuits. One of my brother novices wound up serving on the committee that prepared GU’s apology of last week. Here he is, reflecting on the committee’s work:

A young man named Matthew Quallen wrote a series of articles for the GU newspaper, The Hoya, skewering the university for having benefited from one of the largest slave sales in US history, in 1838. Maryland-province Jesuits had studied the business for years, and had tried to make some amends. Ta-Nehisi Coates of The Atlantic certainly helped precipitate GU’s decision to address this issue in this way at this time.

In other words, Georgetown University has certainly achieved a great victory in political correctness. But: The way GU and the Jesuits have done it also rings with real, inspiring Christian integrity.

I think US Jesuit superior Fr. Tim Kesicki overstated himself a little bit, apologizing so profusely that his words manage to emphasize the us/them division that Christ came to overcome. Addressing the descendants of the slaves the Jesuits sold, Fr. Kesicki said:

…even with your great grief and right rage, with our sin and sorrow, all will be well…

But we must a. hand it to GU and the Jesuits for having the sobriety, learning, and guts to do this, and b. take up the matter ourselves, for the good of our souls…

Why exactly do we say that slavery is wrong? The Catechism puts it briefly:

The seventh commandment forbids acts or enterprises that for any reason lead to the enslavement of human beings, to their being bought, sold, or exchanged like merchandise, in disregard for their personal dignity. It is a sin against the dignity of persons and their fundamental rights to reduce them by violence to their productive value or to a source of profit. (para. 2414)

The dignity of the person–revealed by Christ–provides the key concept. We cannot romanticize an abstract dream of absolute freedom, which no human being has ever actually enjoyed in this limited, creaturely life we live in the fallen world. But neither can we underestimate the genuine incompatibility between slavery and the Christian concept of man.

German bishop Johann Salier put it like this in his 1830 handbook of Christian morality:

The state of slavery, and any treatment of human beings as slaves, turns people who are persons into mere things, turns people who are ends in themselves into mere means, and does not allow the responsibility of people for what they do, or do not do, to develop properly, and in this way cripples them in their very humanity; hence it is contrary to the basic principle of all morality.

Helpful clarity: slavery is immoral because it destroys the moral independence of a human being. Our moral freedom is our distinctly human treasure.

When, in the period of American history before the Civil War, Georgetown University, and the Maryland province of the Jesuits, found themselves on the altogether-wrong side of this moral analysis, we found ourselves there, too.

When, in the period of American history before the Civil War, Georgetown University, and the Maryland province of the Jesuits, found themselves on the altogether-wrong side of this moral analysis, we found ourselves there, too.

It wasn’t just GU; it wasn’t just the Jesuits, who have now apologized so profusely. It was us.

When I say “us,” I mean the Catholic clergy of the United States.

We had a duty to guide souls to the correct moral analysis of slavery as it was practiced in our lands. And we did not do that.

In the first part of the nineteenth century, we studiously misunderstood and misinterpreted the guidance given by the Apostolic See of Rome. Popes didn’t write encyclicals then, and priests and bishops around the world did not expect Roman guidance the way we do now. But the popes had written and taught a correct moral analysis of slavery.

In 1814 and 1815, Pope Pius VII wrote the leaders of Europe insisting on the unconditional abolition of slavery. He prohibited the clergy from making the claim that the slave trade was permitted.

In 1839, Pope Gregory XVI wrote, in an apostolic letter to all Catholics:

We consider it our pastoral duty to make every effort to turn the faithful away from the inhuman traffic in negroes, or any other class of men. We vehemently admonish and abjure all believers in Christ, of whatever condition, that no one hereafter may dare unjustly to molest Indians, negroes, or other man of this sort; or to spoil them of their goods; or to reduce them to slavery; or to extend help or favor to others who perpetuate such things against them. No Catholic can defend such practices, under any pretext or excuse. (In Supremo Apostolatus)

But we American priests (and bishops) did not make the pope’s pastoral zeal on this matter our own.

Now, we did, in fact, find ourselves between a rock and a hard place. No one can hold the Catholic clergy responsible for setting up the chattel-slavery system in America in the first place. The first bishop in the US, John Carroll, freed the slaves he had inherited from his family.

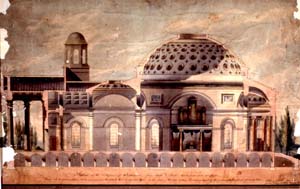

And, when the American bishops began meeting regularly to discuss things in the Baltimore basilica (built by the same architect who gave us the US Capitol)–the series of meetings which eventually gave rise to the greatest book ever written in English, the Baltimore Catechism; when the bishops met in Baltimore, they had some pretty tricky things to discuss, like: how to defend ourselves from the widespread belief that all Catholic priests secretly conspired in a plot for the pope to take over the country.

As Robert Emmett Curran put it in “Rome, the American Church, and Slavery:”

The nativism of the 1830’s through the 1850’s made the American Church all-too-conscious of its status as an alien minority in America. By 1850 Catholics were still less than nine percent of the population, but, having become the largest denomination in the country, were under stronger attacks than ever. Self-preservation became the priority. The bishops as a group concentrated on private behavior rather than social ethics. Except for the area of public education, the bishops foreswore any activity that could be deemed political.

We cannot, however, proffer any of this as a reasonable excuse. Because, in striving to protect our fledgling institutions, we missed the issue. Anti-Catholic bigotry in antebellum America did indeed cause us some problems. But the major problem for everyone in the United States was patently obvious: slavery. Slavery was simultaneously the great moral problem and the great political problem.

We were silent. Former-President, and Virginian, John Tyler wrote to his son in 1854, defending the Catholic clergy from the charges leveled by Know-Nothings. He damned us with this praise:

The Catholic priests have set an example of non-interference in politics which furnishes an example most worthy of imitation on the part of the clergy of the other sects at the North.

…Now, let’s not oversimplify. The North had racism every bit as vicious as the South. Many northern abolitionists insisted both that the Southerners must free their slaves and that those slaves should, under no circumstances whatsoever, come north.

Solving the great moral and political problem required more than slogans and self-righteousness. And the problem deserved a better solution than it got. If we think that the process of brutal Civil War-Reconstruction-Jim Crow-Civil Rights Movement-what we have now illustrates the MLK/Obama principle that “the arc of history always bends toward justice,” then we kid ourselves. Sin doesn’t go away on its own; racism gets born anew in every generation. We need heavenly medicine.

But how can we Catholic clergy not acknowledge that we failed in the early nineteenth century? We failed to apply the principles of Christian morality properly, and we isolated ourselves by our obtuseness. Priests came from Ireland to the U.S. during that period, and they were appalled. Appalled that their brother priests in America tolerated slavery as practiced in the South, without a peep.

Roman authorities had tried to enlighten our consciences, but we knew better. We didn’t like slavery, but we did not regard it as our task to confront its evil.

What task, then, other than confronting such un-Christian evil, could we have claimed to have had? Or what task, other than that, do we have now?

We priests stand at the altar, and we read, and we pray. We must also apply all that we read and pray to the lives of our people, who do their daily business on the little stretches of earth that make up our humble parishes. We must know intimately the physical reality of those stretches of earth.

In one of his articles for The Hoya, Quallen described the lot of a slave that the Jesuits had sold down the river. Cornelius Hawkins wound up working the “fetid, unforgiving fields” of Iberville parish, Louisiana.

Quallen knows how to write. “Fetid, unforgiving fields.”

In the first part of the 19th century, we lost sight of that particular physical reality, and the moral evil attendant to it. It was an evil we had the duty to confront.

The question for us now is: What evils have we lost sight of in the early 21st century? What campus building somewhere will someday have to be renamed, because the honoree wouldn’t focus his or her mind on what an abortionist’s knife actually does? Or on what it’s like to wind up in an ICE detention center?

I am sorry that we failed so miserably in antebellum America. Please God we learn something from the mistake.