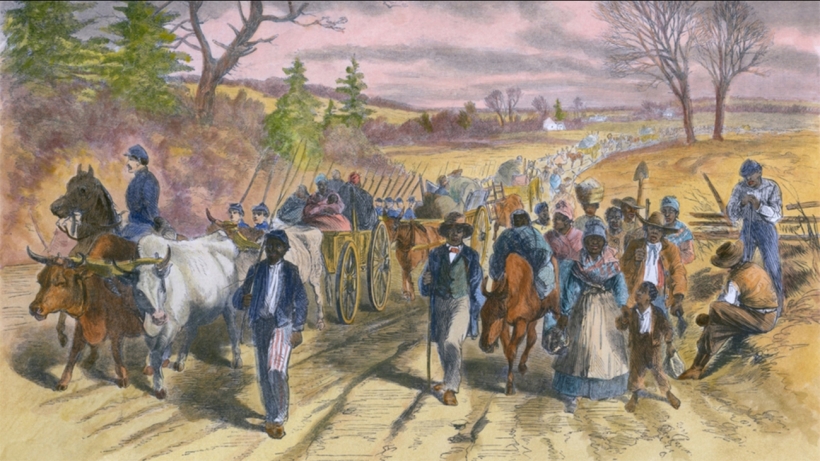

Today we Americans commemorate the end of slavery here in our country. Word of Union victory–and emancipation of the quarter million slaves then living in Texas–reached Houston on June 19, 1865. Jubilation filled the streets.

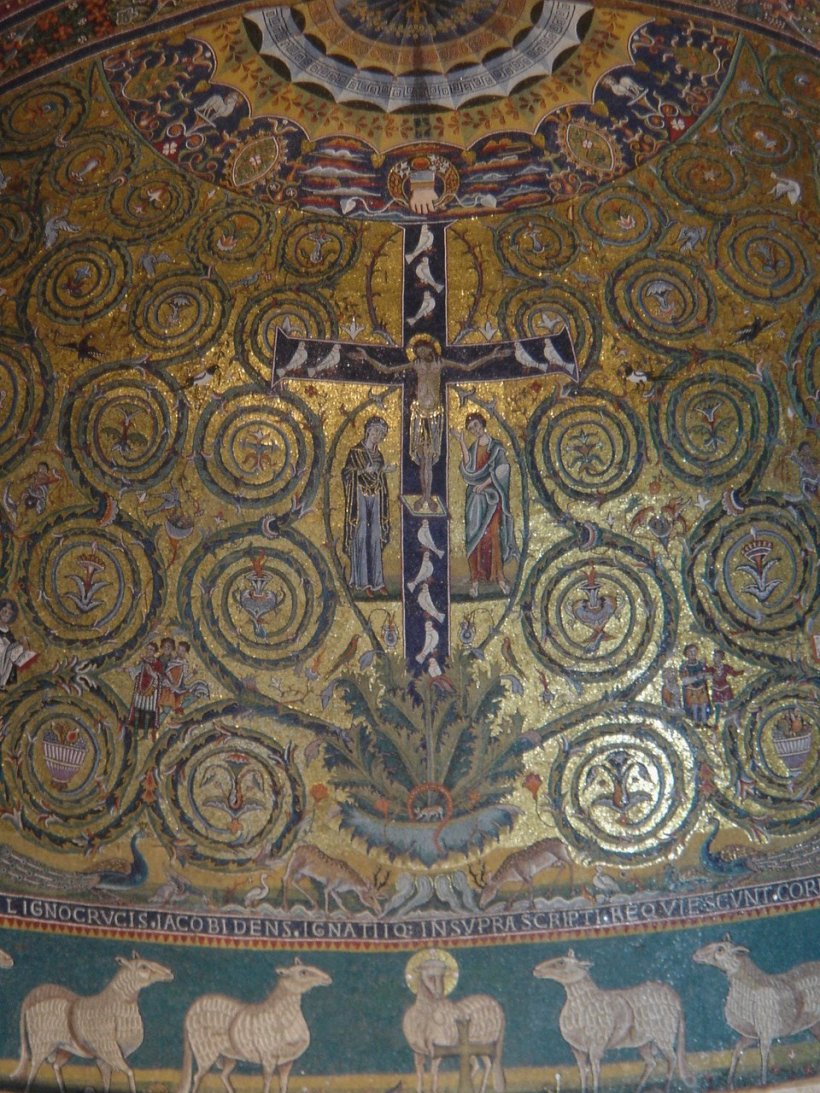

Lord Jesus came into this world to liberate. He came to free every human soul from bondage. To turn us toward the infinite horizon of heavenly love. To teach us our true destiny–and how to achieve it, by loving God and neighbor.

Christians respect the dignity of every human person, made free in the image of the sovereign God. Our heavenly Father summons all of us to eternal love. We recognize everyone’s right to respond freely to God’s call.

From the Catechism:

The seventh commandment forbids acts or enterprises that for any reason lead to the enslavement of human beings, to their being bought, sold, or exchanged like merchandise, in disregard for their personal dignity. It is a sin against the dignity of persons and their fundamental rights to reduce them by violence to their productive value or to a source of profit. (para. 2414)

From an 1830 Handbook of Christian morality, written by a German bishop:

The state of slavery, and any treatment of human beings as slaves, turns people who are persons into mere things, turns people who are ends in themselves into mere means, and does not allow the responsibility of people for what they do, or do not do, to develop properly, and in this way cripples them in their very humanity; hence it is contrary to the basic principle of all morality.

Two years ago, Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., acknowledged with shame, sorrow, and contrition, the fact that the University, and the Georgetown Jesuits, had trafficked in slaves. Among other acts of reconciliation, the University renamed one of its buildings. It had borne the name of Fr. Thomas Mulledy, SJ, who had engaged in the slave trade. Now it bears the name of one of the slaves he traded.

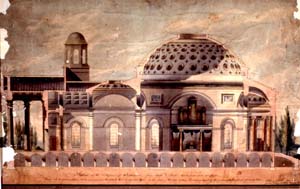

A Virginian, Father Mulledy played a significant role in the early life of the Catholic Diocese of Richmond. He participated in the solemn consecration of St. Peter’s church in Richmond in 1834.

The following year, one of Mulledy’s brother Jesuits, Father James Ryder, spoke at St. Peter’s on the subject of slavery. He spoke to assure everyone that the Catholic Church by no means opposed it.

In what was then the cathedral of our diocese, Father Ryder referred to abolitionists as “wicked would-be philanthropists,” with whom “only madmen or traitors” would co-operate.

Of the abolitionist movement, Ryder declared: “The Catholic will shrink from shaking the polluted hand that would sow the seeds of confusion and horror in the fair fields of the South, rifling the domestic happiness of the master and his slave. [Abolitionism] is not religion. It is not piety. It is a profanation of the gospel.”

Pope Pius VII erected the Diocese of Richmond in 1820, but we did not have a resident bishop until 1841. Bishop John England of Charleston, SC, served as a de facto spiritual leader. But he did not prove to be a genuine spiritual leader at all, on the subject of slavery.

In fact, Bishop England died, in 1842, while in the process of explaining to the world that Catholics do not oppose slavery. Even though the pope had declared in 1839 that we do. Even though the great Irish statesman Daniel O’Connell had challenged his Irish countrymen in America to oppose the servitude of their black brothers and sisters.

Frederick Douglass traveled to Ireland to hear O’Connell. Douglass said that O’Connell had “shaken American slavery to its center.”

But Bishop England, and the American Catholic Church as a whole, not only failed to take up O’Connell’s challenge, but proceeded to impugn O’Connell’s judgment, and to pile up spurious distinctions to defend the enslavement of black people in the South.

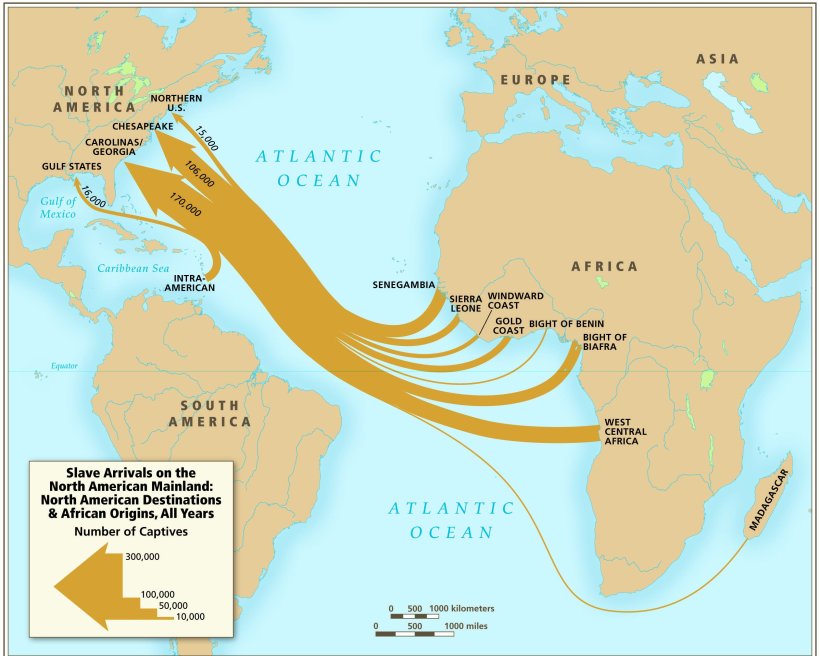

The typical historical narrative regarding American slavery neglects one crucial set of facts. In the early nineteenth century–over fifty years before the Civil War–our mother nation of England actively sought to bring slavery to an end, throughout its entire sphere of influence. The Holy See intervened repeatedly to aid this effort. Most of the western world had come to recognize that slavery offended the dignity of man.

The western world, that is, minus the United States. Andrew Jackson and his partisans pushed in the other direction. The United States took away from the Creeks, Choctaws, Cherokees, Seminoles, and Mexicans, the land that became Florida, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas–in order to expand chattel slavery. The doctrine of Manifest Destiny provided the mythological cover necessary to mask the brutal immorality involved.

All of this happened during the nascent days of both our diocese and of the American Catholic hierarchy as a whole. Bishop England bragged about how the American bishops, assembled in Baltimore in 1840, did not regard slavery as immoral.

Now, we must note that the Catholic Church occupied an almost unimaginably weak position in American society at that time. Bigoted mobs subjected us to repeated acts of violence and arson. And the South had so few Catholics that everyone reasonably wondered if Catholicism could survive here at all.

But all that does not change the fact: We American Catholics profoundly failed to confront the evil of slavery. Our Church not only absented herself from the abolitionist movement; we not only ignored the moral clarity provided by leaders like Daniel O’Connell–we actively opposed the cause of justice for the slaves.

We cannot honestly commemorate the 200th anniversary of the founding of our diocese without acknowledging this lamentable fact.

You can’t erase God’s truth, no matter how hard you might try. Something blinded Nathaniel Russell to the obvious. He had built his comfortable house not just on sand, but on sin. The grave, detestable sin of human slavery ran like rainwater through the streets of his town.

You can’t erase God’s truth, no matter how hard you might try. Something blinded Nathaniel Russell to the obvious. He had built his comfortable house not just on sand, but on sin. The grave, detestable sin of human slavery ran like rainwater through the streets of his town.

When, in the period of American history before the Civil War, Georgetown University, and the Maryland province of the Jesuits, found themselves on the altogether-wrong side of this moral analysis, we found ourselves there, too.

When, in the period of American history before the Civil War, Georgetown University, and the Maryland province of the Jesuits, found themselves on the altogether-wrong side of this moral analysis, we found ourselves there, too.

Work gets us out of the house, engages us with others, challenges us, and brings out our powers and our talents. Work gives us a worthy venue for spending our strength and our time.

Work gets us out of the house, engages us with others, challenges us, and brings out our powers and our talents. Work gives us a worthy venue for spending our strength and our time. Now, many workers suffer unjust abuse of their energies and skills, working under inhuman conditions for inadequate compensation. Others languish in a miserable state of idleness because someone somewhere acted selfishly or meanly—and broke the great chain of relationships that is supposed to keep all able-bodied people working. Other workers have no joy whatsoever in their daily labor, either because they neglected their own education, or because they never had the chance to obtain one.

Now, many workers suffer unjust abuse of their energies and skills, working under inhuman conditions for inadequate compensation. Others languish in a miserable state of idleness because someone somewhere acted selfishly or meanly—and broke the great chain of relationships that is supposed to keep all able-bodied people working. Other workers have no joy whatsoever in their daily labor, either because they neglected their own education, or because they never had the chance to obtain one. The good Lord gave us two things in the Garden of Eden, both of which were designed to lead simply to our fulfillment and happiness. As a race, we human beings have managed to make a big mess out of both of them. We have subjected both of them to our self-centeredness and the worst excesses of our capacity to be ignorant and cruel. Sex and work.

The good Lord gave us two things in the Garden of Eden, both of which were designed to lead simply to our fulfillment and happiness. As a race, we human beings have managed to make a big mess out of both of them. We have subjected both of them to our self-centeredness and the worst excesses of our capacity to be ignorant and cruel. Sex and work.